Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Chinese politics & policy myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

China’s foreign minister has urged Australia not to let “any third party” disrupt the stabilisation of bilateral relations in the first high-level visit by a Chinese official in seven years as the two countries seek to restore relations that dived during the pandemic.

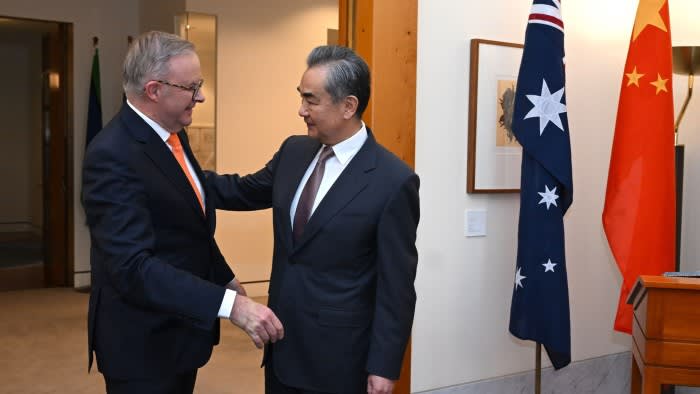

Wang Yi’s comments, a thinly veiled reference to US and Australian efforts to strengthen their military alliance in the face of a more assertive China, came as the minister met Australia’s leader Anthony Albanese and foreign minister Penny Wong in Canberra on Wednesday.

The visit was the latest move to ease tensions that erupted under the previous Australian government and culminated in China’s imposition of tariffs and sanctions on Australian products including wine, coal, barley and beef in 2020.

Australia signed the Aukus security partnership with the US and UK during that period to overhaul its defence strategy and adapt to China’s military build-up. It has continued with Aukus despite the Albanese government’s efforts to stabilise relations with China, its largest trading partner, since taking office in 2022.

Wang said in his opening remarks in the meeting with Wong that he trusted that independence was a fundamental principle of Australia’s foreign policy and that the development of relations between the two countries after a decade of “twists and turns” should not be disrupted or affected by “any third party”.

“The improvement of the relationship between China and Australia . . . can be seen as some kind of breakthrough,” said Wang Yong, professor at the School of International Studies in Peking University, adding that Australia, through its role as a close ally of the US and important trading partner of China, could play a greater “moderating role between the major powers”.

Wang’s Canberra visit, which comes ahead of an expected trip by China’s number-two official, Premier Li Qiang, in June, fuelled hope of more progress on several trade disputes between the two sides. China is expected to lift punitive import tariffs on Australian wine, and the Australian government dropped an anti-dumping complaint over Chinese-made wind turbines ahead of the foreign minister’s visit.

Wang’s rhetoric on Australian “independence” from US policy echoes China’s approach to European countries, which it often urges to follow their own interests and not be influenced by alleged American pressure.

Flash points remained during the talks. Wong said she had exchanged “frank views” with Wang including over the death sentence for Yang Hengjun, an Australian citizen who was detained on espionage charges in China in 2019.

She said she raised concerns about human rights in western China’s Xinjiang region, as well as in Tibet and Hong Kong, and “about unsafe conduct at sea” — a reference to incidents involving the Australian and Chinese militaries.

Wong also said the government pushed for the final trade restrictions on Australian beef and lobsters to be lifted and that she had discussed the volatility in the nickel market, which Chinese-backed mines in Indonesia have dominated. “Predictability in business and trade is in all our interests,” she said.

Richard McGregor, senior fellow at the Lowy Institute think-tank, said China wanted “to go further and add more ballast to the relationship”. “They want Australia to be more quiescent, or silent, on human rights and territorial issues like the South China Sea,” he added.

Wang is expected to meet former Australian prime minister Paul Keating in Sydney on Thursday. Keating has been publicly critical of Aukus, Wong and Labor’s approach to China relations.

McGregor said it was not unusual for China to seek out “old friends” such as Keating and said Wang could highlight the former leader’s views. “It comes at a time when Keating has been critical of Australian foreign policy and vituperative towards Penny Wong,” he said.

Chen Hong, professor at the Australian Studies Centre of East China Normal University, said it would be difficult for relations to return to what they were previously despite the positive signals.

“You can never step into the same river twice,” said Chen. “The world is changing and the geostrategic scenarios are quite different.”

He said China understood that Australia was allied with the US, but Canberra’s pursuit of Aukus was a more direct challenge to Beijing.

“Aukus as everyone knows presumes China to be the adversary, so by engaging actively in this pact, any country in that pact is positioning itself on the opposite side of China [and is] putting China in that adversarial position,” he said. “So that would of course definitely impact on China’s vision of that country, in this instance, Australia.”

This post was originally published on Financial Times